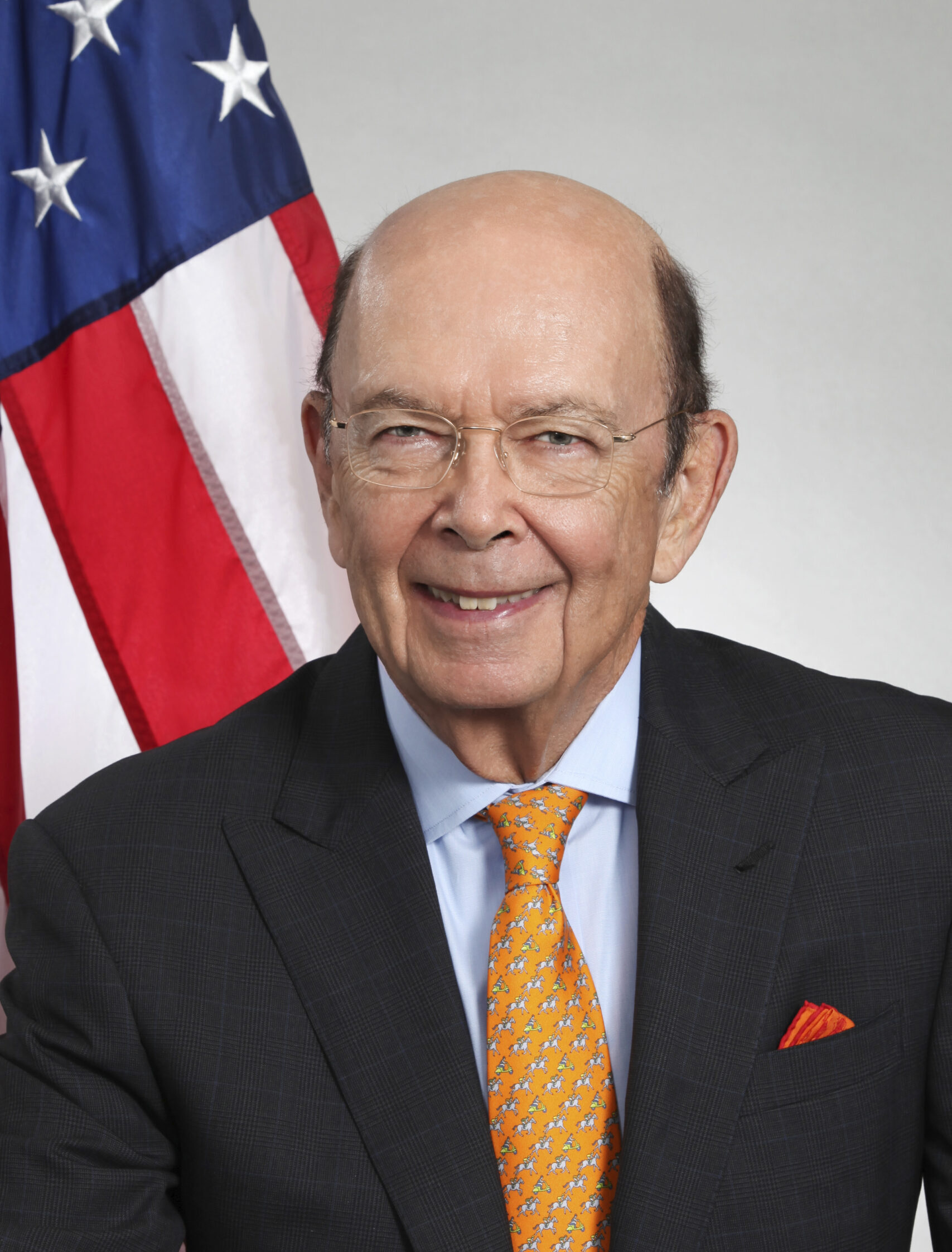

Wilbur Ross On How Trump’s Tariffs Impact CEOs and CFOs

In the second part of Global Finance’s conversation with former US Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross—who served during President Trump’s first term—the discussion shifts to the impact of Trump’s tariffs and trade policy on CEOs, CFOs, and key trading partners like Canada, Mexico, and India.

Global Finance: What would you recommend to CEOs and CFOs navigating this climate of uncertainty due to US tariffs and trade policy as they determine their near- and long-term strategies?

Wilbur Ross: Yes, reshoring and nearshoring were some things that would develop momentum in any event. President Trump is going to accelerate that.

Whatever plan people had for relocating production, it would be wise to accelerate it. Now, whether that means moving operations to Mexico or the US, that’s another question. But the days when a company could make one component in one country, a second in another, and a third in yet another—then bring them all to a fourth country for assembly—are ending.

Therefore, it should be more of a question of to what degree you relocate facilities and whether or not to do so, and to a degree where to relocate them. The rules of origin will be much more important to Canada, but particularly to Mexico, than before. So, as long as one incorporates that into their thinking, I think relocation is the wise move to make.

GF: Is the message different for CEOs and CFOs outside the US?

Ross: Yes, it could be if they adopt policies similar to Trump’s. We are moving toward an era where what has been called “protectionism” becomes much more of a centerpiece of everyone’s trade policy. But what Europe must do to be effective is to deregulate some. The regulatory burden that European governments impose on their companies is a real impediment to reshoring. Europe has become too intrusive in the business community.

Trump has also said he will require his cabinet members to cancel an even higher ratio of existing regulations relative to any new ones they implement—higher than what we had the first time. The first time, you were required to cancel two for each one you put in. He may be pushing for as many as eight, but certainly more than two. That’s one thing.

Tax policy is the other thing. You have to look at Trump’s trade activities in the context of what he is doing overall. Between deregulation and reducing corporate taxes, he’s changing the economic attractiveness of being in the U.S. regardless of tariffs. And then when you load on top of that, a bit sturdier tariff policy, you have a combination of factors that will prove very powerful.

GF: Which means that you also think this will be the outcome of the current situation?

Ross: Okay, well, there will naturally be a lag. You can’t build a new facility of any size in 10 minutes. There may be some near-term dislocation as we face higher tariffs, but we don’t yet have the increased production to offset them.

Now, that’s not a universal problem. Many of our industries operate at only 70–80 percent capacity. Therefore, not only will they be able to meet increased demand, but this will also help them absorb part of the tariff on imported components. When production increases from 70 or 80 percent capacity, the marginal costs are very small. You’ll have that factor and probably another factor—currency readjustment. How that plays out will have an important impact on how well industries do globally in each area.

To that end, if U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell is slow to reduce interest rates while Europe moves at a faster pace, that will clearly have implications for currencies.

One of my concerns for Europe is that if they lower interest rates too quickly relative to the U.S., it could have real impacts on their currency. That would hurt imports but help exports. If I were a European manager, I would be more eagle-eyed than ever about the outlook for currency fluctuations.

GF: Looking at the various industry sectors, are there sectors that deserve tariffs? Are there also sectors that should not see tariffs in these negotiations?

Ross: Well, I have focused more on those who might need it than those who might not. However, pharmaceuticals are a big import to the U.S. Since U.S. drug prices are already higher than others, I don’t think hefty tariffs on pharmaceuticals would be particularly well-fitting to our economy.

But they’re going in on the really big item—the automobile. Automobile manufacturing has caused a fair degree of factory expansion here and in Mexico. In the automotive industry, you must look at the U.S. and Mexico combined because of the concept of rules of origin. In those areas, it’s inevitable. So, I think you’re right—it will vary somewhat by industry. But for the most part, most manufacturing businesses probably don’t expect there will be more tariff burdens.

GF: Would large U.S. exporters, such as technology manufacturers, be affected negatively by this?

Ross: Well, Europe doesn’t have the technological content we have so far. The giant companies in Europe are not comparable to what we call “The Magnificent Seven” over here. Europe’s response seems to have been antitrust and tax complaints, trying to hold back American companies rather than doing things that would effectively build up a European champion.

GF: What of those U.S. industry sectors geared more toward exports? Are they at risk because of tariff reciprocity in the near term?

Ross: Well, apparel is a significant import from Asian countries, and it wouldn’t surprise me if that were to continue. Some of those brands, such as the European brand Zara, have become very, very powerful players in the US. It’s a Spanish company, but it mainly produces its material in Turkey. Meanwhile, Vietnam and Mexico have become big competitors in what we used to call sneakers. So, some things will remain there that will not be affected by the tariffs.

But remember, the real purpose of the tariffs—and one that I hope will be achieved long term—is to let the rest of the world know exactly what they must do to bring our tariffs down, namely, to bring down their own tariffs. The unexpected result of the new US tariff policy could very well be lower tariffs in the long term.

Take India, for example. India’s tariffs are extremely high on most products. Prime Minister Narendra Modi wants to industrialize India. It’ is a logical place to be competitive with China if they can meet their infrastructure needs, because Indians have very good quality manufacturing skills, technological skills, and engineering skills. They have a large population base, so there’s no reason they can’t compete. What’s been holding them back has been the need for more roads and railroads. You need things like that in the way of transportation infrastructure to be much more highly developed for India to flourish. There’s a good chance that PM Modi will do that.

Vietnam has already benefited greatly from the pressures being put on China, which will probably continue. However, Vietnam has a much smaller economy and population base, so it can’t remotely replace China.